In EI2, we have lots of roles. Coaches. Consultants. Analysts. Service coordinators. Lots of things. But we can never forget that we work for a university. And universities are in trouble.

I was able to spend part of two days last week with Rich de Millo, former Dean of the College of Computing, and now the director of Georgia Tech’s Center for 21st Century Universities He spoke at Homecoming to a packed house of GT alumni about his new book “Abelard to Apple: The Fate of American Colleges and Universities.” I took notes, and want to share some of his thoughts (and mine) with you.

The MOOCs are coming!

An acronym only a computer hacker could love: Massively Open Online Course. This is not your father’s Distance Learning. How massive? Well, there are 130,000 living Georgia Tech alumni. In the last month, we have registered another 121,000 students for our first six MOOCs to be offered on the Coursera platform.

Now, is taking “Health Informatics in the Cloud” from our very own Mark Braunstein going to be as effective online as in the classroom? We’ll know in a few months. And I expect it will always be better to be one of forty people in a room with Mark Braunstein than to be one of 10,000 MOOC participants.

But.

I expect that being one of those 10,000 MOOC participants will still be a very effective learning experience. It will probably be more effective than taking a course with the same title from a $50/hour adjunct professor at a second- or third-tier university. And it will definitely be more effective than being stuck with the course catalog of your local community college that doesn’t offer an equivalent course at all.

And that changes the world.

De Millo points out that the U.S. went through a huge period of experimentation with the number, size, and types of universities in the period between the Civil War and World War I. We created literally hundreds of universities from raw dirt… sometimes, lots of raw dirt (see the history of land grant universities). (Georgia Tech was founded in the middle of this period.) And then we stopped.

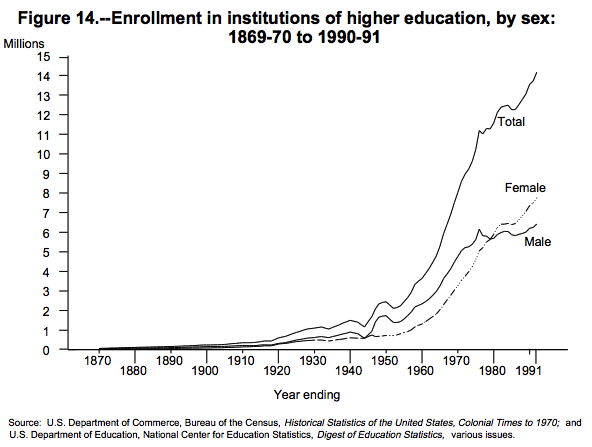

We didn’t stop sending kids to college, of course. We sent more and more and more. The “hockey stick” below is amazing. But we stopped innovating in what a college or university should look like: Big lecture halls for freshmen, smaller classrooms for upper-level courses, a four-year race to a bachelor’s degree, then another more leisurely pursuit of a graduate degree, all overseen absentmindedly by the “sage on the stage” with a blackboard and a piece of chalk. (An iPad with an LCD projector is nothing more than a high-tech blackboard.)

By any measurement — enrollment, debt, opportunity cost, public confidence in the value of a degree — higher education has been on an unsustainable path for at least 40 years. And now, higher ed looks like the next wheezing obsolescent industry to be utterly transformed by the Internet.

Suddenly, traditional universities are not the only game in town. We saw the first rumblings with the popularity of DeVry, Strayer, and the University of Phoenix. But those for-profit entities, while making portions of their content available online, still have campuses… and still charge tens of thousands of dollars for a degree.

Now, with MOOCs, a university-level education is available for free. Often taught by the very best professors in the world. And, to misquote Mark Twain, the difference between the best professor and a mediocre professor is like the difference between the lightning and a lightning bug.

With everyone in the English-speaking world able to put content online (check out the completely unaccredited Khan Academy), it’s going to be a crowded market. In a crowded market, you need a compelling product or a compelling price or a great brand. Most universities have none of the above. (Georgia Tech is lucky — I’d argue that we have all three. But what about East Wherever State U.?)

A lot of universities are going to go out of business. And they should.

Universities are a Failed Model

The great expansion of American universities coincided with the Gilded Age of American industrialization. It’s not a coincidence that two of the buildings on Georgia Tech’s historic campus are named after Andrew Carnegie (steel) and Solomon Guggenheim (mining). Nor that two of our national rivals are Carnegie-Mellon and Stanford (railroads). The Industrial Revolution created unprecedented wealth in America, and the beneficiaries contributed a lot of it to the new universities.

These philanthropists had made a lot of money with factories. And, by osmosis, the American university began to resemble a factory. Not physically, of course — although you might think differently when the Georgia Tech steam whistle blows to mark the changing of classes! But universities standardized on batch processes (a new batch of freshmen every fall), mass production (the same sequence of required courses for each student in a given major), quality maintained by inspection (exams), and a big reject pile (students who failed their exams, or who gave up, or who were deterred from even entering).

Ask any member of the MEP program here in EI2 and you’ll find that trying to achieve quality through inspecting the end product is a lousy way to run a process. Quality begins at the design and specification phase, with multiple layers of feedback loops all the way through to the finished product. And that’s where MOOCs re-enter the picture.

Feedback Loops

What’s the feedback loop for a modern university? Students graduate. Employers notice that they’re missing certain skills, so they implement remedial on-the-job training. The employers complain to the university’s upper management. Messages drift down to academic departments on a multi-year schedule based on the appointment of new deans and school chairs. Occasionally, there is a curricular spasm designed to make the degree more “relevant.” But “it’s easier to change the course of history than it is to change a course in history.”* Years later, after mossbacked professors retire, the curriculum changes. By which time the demands of industry have changed. And so it goes.

Sebastian Thrun, the world-renowned computer scientist best known for designing Google’s self-driving car, launched one of the world’s first MOOCs from his position on Stanford’s faculty one year ago. 160,000 students worldwide enrolled. And feedback loops emerged. When students were having difficulty with a particular approach, the online tools let Thrun understand the gaps and make adjustments within a week. Not years.

Feedback loops matter.

Lots of people talk about MOOCs the way they used to talk about “distance learning” — basically a way to cut costs and deliver education to those who can’t afford it. That will happen, but that’s not the point. With feedback loops and competition for student attention, MOOCs will evolve through a brutally Darwinian process. The best courses and instructors will attract more students. The not-so-good will wither away. There will be a relentless downward pressure on prices but an upward pressure on quality. Thrun has even gone so far as to say that there will only need to be 10 universities in the world.

I disagree — national and regional pride will still play a part — but my opinion isn’t important. What’s important is that the best universities in the world are stepping up to try to improve the quality of education by leveraging these new tools. The leaders are arguably Stanford, Harvard, and MIT. But Georgia Tech is a fast follower, and I wouldn’t be surprised if we break into the lead. Stay tuned.

Who Pays For All This?

The current view of MOOCs is that they’re free to anyone with a web browser and an Internet connection. And I think that will continue to be true. But there’s a difference between learning the material and having someone else believe that you’ve learned the material. So there will be a role for testing and certification services. Instead of spending four years on a particular college campus, you may spend four years (or six… or two) collecting “badges” that certify your mastery of certain material.

Will the accreditation bodies accept this? Will anyone care if they don’t?

And the certification service (maybe Georgia Tech, maybe Kaplan) has an interesting new line of business — selling contact information for the best students to employers. The recruiting business is about to get kicked in the head.

Students who can afford it may want to spend a couple of years on campus, if only for social reasons. But if the average undergraduate chose to spend two years in residence rather than four, Georgia Tech could double enrollment without building a single new classroom or dormitory. That’s interesting.

And will they still think of themselves as Georgia Tech alumni? What does that mean to our philanthropic development programs?

May You Live in Interesting Times

In EI2, we’ve seen thousands of clients in dozens of industries disrupted by sudden technological change. First it was textiles. Then light manufacturing. Then heavy manufacturing. Then computer programming. Then design and consulting work. In every case, technology enabled brutal worldwide competition, and the inefficient were decimated or worse.

Now it’s higher education’s turn. And it couldn’t come a moment too soon. De Millo ended his talk with the statement that “If you started with a clean sheet of paper and tried to design an environment that would blunt creativity, destroy enthusiasm, and limit learning, you’d probably come up with what we have today.”

We can do better. And we can save money in the process. No one has asked EI2 to apply value stream mapping to a undergraduate curriculum — yet. Don’t be surprised if it happens soon.

* I wish I knew who to credit with this delightful quote. Sadly, it’s not me.

I think it’s quite a bit of an exaggeration to suggest that MOOCs would “probably” offer a higher quality education than community colleges. I’m not sure if you’ve taken a course at a community college, but the general consensus among those who have is that the teachers are often very good. They have advanced degrees in their fields, but most importantly they are passionate about teaching. They’re also very accessible because community college class sizes are smaller. How can you say that a MOOC could do better than that simply because the professors are well-known in their fields? How many Stanford mathematicians were hired for their ability to very clearly explain calculus concepts to students?

I think it’s a bit too soon to praise MOOCs for offering education to those who may not otherwise have access. If you sign up for a course on Coursera and check out the introductions, you will find that many (seemingly the vast majority) of the students fall into one of three categories: college-bound high school student, college student, and working professional. These people are using Coursera to get a head start on a course they will take, as a supplement to courses they’re already taking, or to brush up on a course related to their field. These courses are definitely a great resource for those who take them, but I struggle to see how they will be transformative.

There is no doubt that university tuition rates are getting absurd, but until MOOCs find a way to offer a propulsion lab, I’m skeptical that they’ll offer much more than what AP credits do – another way to get Calculus and History out of the way.