A couple of weeks ago, I was fortunate enough to be invited to an internal lecture at Mailchimp, right across the parking lot from our AMAC team. (If you aren’t familiar with Mailchimp, they rock! Great solution for any sort of email marketing or email list management. Better than Constant Contact, and local!)

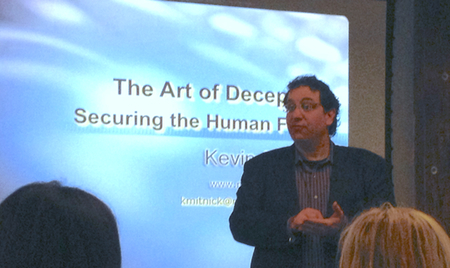

The speaker was Kevin Mitnick. Some of you will remember his name. In 1995, just as the Internet was breaking into public consciousness, he was the most-wanted computer criminal in the U.S. He was arrested and served five years in Federal prison. He served some of that time in solitary confinement because law enforcement officials convinced a judge that he had the ability to “start a nuclear war by whistling into a pay phone.” A movie about his exploits, Takedown, was released in 2000. Unsurprisingly, he now runs a computer security consulting firm.

Kevin spoke for over two hours on “The Art of Deception.” The core message: as computer security systems have gotten more and more sophisticated, the easiest way to break into a system is to exploit the weakest link — human beings.

While relatively unknown to the general public, the term “social engineering” is widely used within the computer security community to describe the techniques hackers use to deceive a trusted computer user within a company into revealing sensitive information, or trick an unsuspecting target into performing actions that create a security hole.

Mitnick illustrated why a misplaced reliance on security technologies alone, such as firewalls, authentication devices, encryption, and intrusion detection systems are virtually ineffective against a motivated attacker using these techniques. In fact, he stated that when his security company is permitted to use “social engineering” in penetration-testing a company, their success rate is 100%.

One hundred percent.

So, unlike the Hollywood portrayal of hackers, the risk isn’t someone guessing your password; it’s you giving it to them. (Or the Help Desk resetting it, thinking they’re serving a legitimate request.)

One of my favorite quotes was “We can’t go to Windows Update and download a patch for stupidity.”

And it’s not idiotic things like writing down your password and taping it to the bottom of your keyboard (because the bad guys would never look there!). It’s the natural human impulse to try and help others, especially when they’ve done their homework and have a convincing story to tell you. (Kevin is obviously a gifted actor… which is why some of his most successful hacks were done face-to-face or over the phone.)

Just one example: spam an entire company, and monitor for vacation autoreplies. Okay, Pat will be on vacation until next Friday. Use LinkedIn to find Pat’s boss, Michael. Call Michael, hit zero, get transferred to his admin, Tracy. You already know Tracy’s last name and location from the corporate website, and you’ve picked another location in the same organization but a different city. “Hey, Tracy, it’s Kevin, in the Northwoods office. I work for David Lippanzer. Is Pat on vacation already? Darn, she promised to send me the most recent sourcecode file before she left. Do you have it?”

Follow through a few more steps in the script, and nine times out of ten, you’ll have the target document arriving in your email about the time you hang up the phone.

Similarly, try the Help Desk. Call and impersonate someone you’ve researched, and ask for a password reset. There will be a security question. If your research uncovered the answers, proceed. If not, fake an interruption, go do more research, and call back once you know the answer; the question won’t have changed. High school, mother’s maiden name, last four digits of your SSN… all of these are available quickly and easily over the Internet.

(As an aside: Kevin asked for a volunteer to come up from the audience. Given full name, approximate age, and the fact that he lived in Georgia, it took less than three minutes to come up with home address, cellphone number, Georgia driver’s license number, and Social Security Number.)

How about SMS? Do you ever question the Caller ID of an SMS message? What if you got an SMS from your boss, saying “When Kevin calls, email him the new price list. Don’t call back, I’m in a meeting”? Would you do it? He demonstrated exactly that, spoofing phone numbers selected at random from an audience member’s phone.

Or the incredibly low-tech route: dumpster diving. Digging in a dumpster is usually not illegal, although it can get awfully messy. (Kevin: “If you find a plastic bag that sloshes, put it aside. Trust me.”) And the first thing to look for is printer paper torn in half or quarters; that means there was something on those pages worth looking at. This is a great way to get internal phone lists, release calendars, and other information that may not be all that sensitive, but can really help building a credible background story when calling for the real target info.

More complicated hacks: sending you a phishing email from Citibank, and listing an 800 number that is similar, but not identical, to the number on the back of your card. If you dial that number, you are connected to the bad guy’s voice-interactive server in the Ukraine… so it calls Citibank, feeds you the prompts, collects the Touch-tone responses from you, and feeds those to Citibank. Classic “man in the middle” attack — and you have no suspicion that you’re actually connected to anyone but Citibank, since you can check your balance, verify your last transactions, or transfer money, and get all the correct responses.

Of course, as soon as you hang up, the bad guy’s server calls Citibank again and, with your stolen credentials, initiates a very different transaction.

How about a $25 box the size of a cellphone charger that you plug into a power outlet at Starbucks? It collects every password and every secure transaction conducted over that Wi-Fi network. And, since it’s $25, you don’t even have any risk of being caught when you go to retrieve it. You plug it in, collect the data remotely, and abandon it to be found by the cleaning crew that night. (Or not.)

There was lots more. (If you found a USB drive labelled “2013 Payroll Info” by the bathroom sink, how many of you would be able to resist putting it in your computer before turning it in to someone? Whoops, a team of Romanian hackers now has complete and total control of your computer. And you’ll never even know it. This is how the Stuxnet virus was spread through tightly-secured nuclear facilities in Iran.)

It was a scary couple of hours. But beyond “Be Alert!”, one key message was “Use technology whenever possible to take decision-making out of your employee’s hands.” Because humans want to help other humans; that’s hardwired into us. And, as a first approximation, we tend to trust complete strangers. (If not, we’d never get through a four-way stop sign alive.) And those natural human instincts are the weak link in modern computer systems.

So if someone who lives in Atlanta is calling Citibank, but the call is being routed through the Ukraine — it’s time to take that call out of the hands of the $12/hour front-line call-center attendant. Kick that one to a supervisor, who should intervene with something like “We have three phone numbers on file for you. May I call you back at one of them and complete this transaction that way?” And that shuts down the attack.

(Incidentally, that sort of alert is one of the capabilities of Pindrop Security, a VentureLab startup that’s now in ATDC.)

The cultural change is that it has to be okay to say no. This will lead to the occasional frustration of a legitimate customer — such as when my wife tries to use online banking from her Brazilian bank account while sitting in Atlanta. But the savings in fraud prevention are worth it.

Y’all are too smart to be taken in by a standard mangled-English phishing email:

You need to Upgrade and expand your webmail quota limit before you can continue to use your email.

Update your email quota limit to 2.6 GB, use the below web link and login your full email address and password.

Failure to do this will result to email deactivation within 24 hours

But the real bad guys are a lot more sophisticated than that, and they may show up in your text messages, as a phone call, or even in person. Start thinking of these social-engineering hacks in your personal life, in your professional life, and in processes of the companies that we work with.

Love it. Really makes me want to try some of it to see if it works. But probably not a good idea!

BTW, we now have your signature, so your one step closer to being compromised 🙂