This is a continuation of a previous set of posts and is fourth in a series.

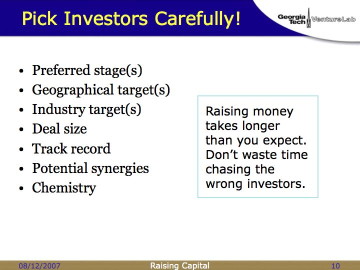

Not all venture investors are created equal. Most firms have specialties. Even within firms, individual partners will have specialties. Don’t waste your time on firms who don’t focus on companies that look like you.

You can read the parameters on the chart above. Pay attention, and do your homework. A lot of this will be documented on the firm’s Web site. You also need to double-check through your personal network to identify firms that are a good fit. Chemistry you can only figure out in person (and, no, videoconferencing isn’t good enough).

There’s a trap here: bigger funds have lots of associates. Associates can’t make a deal happen, but they sure can prevent a deal from happening. So you need to be polite and responsive to them, in the hopes that they get a partner interested.

Maybe that’s not going to happen at a particular firm, even if it looks like a good fit. Maybe the relevant partner is overcommitted at the moment; maybe the firm has decided to take a break and digest things for a while; maybe they just don’t like you. (It happens.) But you’re smart, and you’re passionate, and you (hopefully) are good at explaining your technology and your market. And the associate wants to learn more… not to push your deal forward, but to increase his or her expertise and be better prepared for the next deal.

So the trap is that the associate may keep calling you back for more and more meetings… maybe camouflaging the process by bringing different associates into the mix, or a consultant, or an entrepreneur in residence. You are providing some very expensive training at your own expense (especially if you are buying plane tickets for these meetings!). And you’re no closer to getting a check… indeed, you’re wasting time that you could be spending with a fund that’s serious about you.

Don’t waste time chasing the wrong investors.

One of the most obvious things to check is whether a firm does early-stage or later-stage investing. There is plenty of capital out there—to misquote Harlan Ellison, the two most common elements in the Universe are hydrogen and capital—but most of it isn’t for you.

Most capital is invested in later-stage deals, for the simple reason that later-stage deals require more capital. More on this in the next chart.

If you’re an early-stage deal (and if you’ve read this far in my series, you probably are), you need to make sure your target investors do early-stage deals. This is an area where you can’t just trust the Web site… a lot of investors will claim to do early-stage, but then you dig a little deeper and realize their definition of early-stage is “revenues of $1 million to $5 million.” It’s a long ways down from there to you, your dog, and your patent application.

Use your network. Ask around. Find out what deals the firm has actually done lately. Do they feel like they’re in the same world as you are? If not, keep looking.

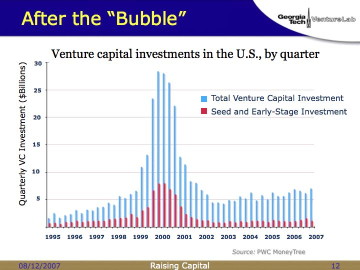

For those of you who haven’t seen this curve, this was the Bubble. Yep, we all went a little crazy in 1999 and 2000. It was fun while it lasted.

But the point of showing it this time is to demonstrate that the percentage of capital allocated to early-stage deals remained relatively constant, even when the dollar volume went to the Moon. Call it twenty percent.

If you’re an early-stage deal, be sure to spend your time with investors who make up part of that twenty percent. It may be flattering to get called by SuperMega Ventures, but the likelihood of a billion-dollar firm investing in your pre-revenue startup is slim.

(Slim. Not zero. Read up on “barbell strategy.” I would attach some links, but a quick Google search is complicated by pages of fitness equipment.)