This is a continuation of a previous set of posts and is tenth in a series.

Earlier I said “Your business plan is a marketing document as much as it is anything else.” As several of us have discussed on Lance Weatherby’s blog, some investors today may not actually read your entire business plan. (They probably will have an associate scrub it, though.) As I commented there,

Writing the business plan is good discipline for the entrepreneur (and good entrepreneurs frequently have a problem with discipline).

Once you’ve finished it, you should distill all that skull sweat into a two-page executive summary and stick the plan in a drawer. Your investors may or may not ask to see it. But your exec summary and PowerPoint/Keynote presentation will be better because you wrote it.

If you’ve done it right, you should have no trouble getting meetings scheduled with venture capitalists. (Really. Trust me. These folks get paid to make investments. If they don’t make investments then, eventually, they don’t get paid.)

You need to make sure you have scheduled meetings with the right venture capitalists, and you may have to buy some plane tickets, but all you have to do is demonstrate your ability to create a business plan that’s in the top 10% of your peers, and you’ll get meetings.

So, first off, congratulations. You’ve done a lot of hard work.

Now do more.

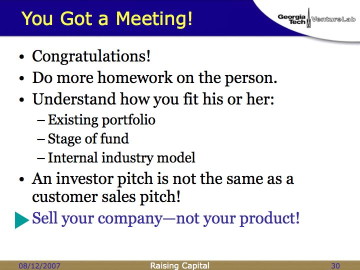

Remember the bit about targeting your investors carefully? If not, go read it. Because now that makes a huge difference. You’re going to go to a meeting, chewing up valuable time for both you and for the VC… it’d better be a good match.

You already learned a lot about the VC firm before you networked your way into sending them a plan. Now you have to learn more about the individual(s), and the current status of their fund.

Individual

You’re not going to go meet with “XYZ Ventures.” You’re going to meet with Joe Tightpockets, or Sally Webtragic, or whoever. Find out who else is going to be in the room beforehand. And now the Google Machine is your friend. Learn everything you can about the individuals… where they went to school, where they worked before they became a VC, which deals they’ve done, which boards they sit on, which non-profits they contribute to, etc. Make some phone calls, explore connections in LinkedIn. Don’t worry about feeling like a stalker. Privacy is overrated.

Current status of fund

In the process of stalking researching your prey potential investor, you have found out a lot about his or her firm. A lot of it looks repetitive and deadly dull. But you need to know this stuff.

You can never step in the same river twice. And XYZ Ventures is never the same investment firm twice.

Existing portfolio

They’re always adding portfolio companies. That’s a two-edged sword for you. VC firms love having synergies between their portfolio companies. That’s because we’re all trying to emulate the glory days of KPCB and their “keiretsu” investing model. So if you can become a part of the supply chain of an existing XYZ portfolio company — or vice versa — you score points. But, if they’ve already invested in a company that’s “too close to your space,” you can see their eyes glaze over pretty quickly. Be aware that their definition of “too close” and yours may be very different.

Stage of fund

You don’t get a check from “XYZ Ventures.” You will get a check from an entity with a name like “XYZ Ventures IV, L.P.” I talked about limited partners earlier… they’re the ones with the money. As the venture firm goes through the cycle, the general partners raise distinct funds, usually distinguished by Roman numerals. If things are going well, the GPs will be managing multiple overlapping funds… in this example, XYZ Ventures III, IV, and V. There are really good reasons to not allow cross-investments between funds, so you’re going to have to match your capital needs to the capital reserves of one of those funds.

Let’s say that XYZ Ventures III is ten years old, IV is six years old, and V is two years old (a typical spacing). Fund III is in “harvest mode”… with luck, they’ve made their numbers with some good IPOs or M&A activity, they’re not making any new investments from this fund, and they’re reserving any remaining capital for follow-on investments to get the stragglers sold off at any acceptable price. Fund IV is nearing the end of its investment cycle, but there likely some capital still available for new investments. And Fund V is wide open, with lots of uncommitted capital.

So, you would be happy with an investment from either Fund IV or Fund V, right?

Wrong. It depends on your stage of development. If you’re raising a Series C round, and you expect that to be the last round of capital you need before IPO or M&A in a couple of years, then you’re a good match for Fund IV. In fact, they’re probably looking for a few deals just like you, with lower return potential but lower risk, to fill out the portfolio and keep the numbers looking good.

If, on the other hand, you’re just starting off with your Series A fundraising, Fund IV would be a terrible investor for you. Because in a year or two, you’re going to need your Series B… and XYZ Ventures IV will now be in its eighth year, and they will be stingy with capital… and by the time you need your Series C, Fund IV will be shutting down, with the last few deals (you!!!) being herded to the auction block, bleating and mooing.

On the gripping hand (you need three hands in this business), Fund III is hungry for good deals, but they haven’t made their numbers yet, so they’re still swinging for the fences. If you come to them with a potential base hit, they may look right past you at the next bright shiny object to come their way.

So, you want to raise Series A money from a young fund, of an appropriate size that your returns will be material in making good returns for the overall fund. It may be Roman numeral XIV, but as long as it’s only a year or two old, they’ll be able to keep investing their pro rata in every round until you get profitable, get sold, or get dumped.

It gets confusing, because all of these funds are “XYZ Ventures” and they’re all represented by the same set of blue-buttoned-down khaki-clad Stanford MBAs, but it’s the sort of thing that you really don’t want to get surprised with down the line.

Internal industry model.

Remember that you’ve been doing your homework, so you’ve probably been able to establish some common threads behind your targeted venture firm. They might have done a bunch of SaaS deals, or maybe they’ve gotten into open-source. You don’t have to fit that model, but you have to understand it… and explain either how you do fit, or how you’re a useful counterbalancing bet. If you’re not pr

epared, then the VC can make some stupid sweeping comment like “But all computing is going to move to the cloud, leaving your rich client orphaned” and you wind up gaping like a fish. If you’re prepared, you can have an intelligent reply and actually lead the VC into a discussion rather than ex cathedra pronouncements.

Why all this homework? It’s to prevent you from making an incredibly common, yet incredibly stupid, error.

Let’s say you and your team (bring one or two other people… don’t go alone, and don’t bring a crowd) have a meeting scheduled in the VC’s office at 2:00 pm. You’re going to be there at 1:50 to allow for getting lost, to scope out the conference room, and to pre-flight the technology. (If you are using a laptop, it should already be booted. If you’re using a projector, it should already be powered on with your first slide on the wall. Even if you still use a PC, you might think about getting a Mac for your presentation work to reduce the possibilities of embarrassing fumbling in front of your audience.)

So a pair of associates are on time at 2:00, and your target VC waltzes in at 2:04. You chit-chat for three minutes about the traffic, if you got your parking validated, and yes, the view from the window is spectacular. It’s now 2:07 pm. The meeting will end at 3:00. And now you open your mouth and say something suicidally stupid.

“Tell me about XYZ Ventures.”

VCs have egos as big as all outdoors; it’s in the requirements spec. So he (or she; ego is genderless) will start telling you about XYZ Ventures. Their history, their investment philosophy, their portfolio companies, their IPOs, their value-added service, their limited partners, their special limited partners, their double-secret extra-special limited partners, their entrepreneurs-in-residence, their Ferraris, their yachts… it’ll probably take 25 minutes until they have to stop for air.

It’s now 2:32 pm. The meeting is still going to end at 3:00. And you have just wasted half of your allotted time listing to this blowhard natter on about information that is all on their Web page!

Imagine a different scenario. You have chit-chatted. It’s now 2:07 pm. Now you say, “I’ve done a lot of reading about XYZ Ventures. I know you’ve invested in three SaaS companies, and that you personally are on the boards of Bloxrog and PurpleGroovy.com. I went to school with Ramit over at Bloxrog, he’s a great guy and I know you like working with him. Let me show you how my company can fit just upstream of PurpleGroovy.com, and why we’d love for XYZ to lead our Series A round.”

That took fifteen seconds. It’s still 2:07 pm, but you now have my full and undivided attention. My Treo stays in its holster, I’m gesturing to my associates to take copious notes, and now you can swing into your 10-20-30 presentation (more on that soon).

I’m 1600 words into this blog post, and I haven’t yet touched on the most important part of this chart, so I’m going to leave that to the next post!

One thing I’ve heard you say before, and which really stuck with me is doing the research on the individual you’re meeting with. Sometimes, firms will have their associates act interested, and keep talking with you, not because the firm is really interested in you, but because they want to use you to train their associates.