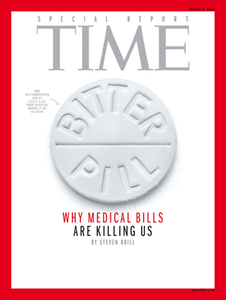

In its March 4th issue, TIME magazine published its “longest single piece ever published by a single writer”: Steven Brill’s article on healthcare costs. It’s available free online, even if you don’t subscribe (click here).

I started reading it, then backed up to the beginning and started taking notes. Brill did a great job of reporting with this piece. You really should read the whole thing, but here are some quotes:

When we debate healthcare policy, we seem to jump right to the issue of who should pay the bills, blowing past what should be the first question: Why exactly are the bills so high?

The health-care-industrial complex spends more than three times [lobbying] what the military-industrial complex spends in Washington.

For every member of Congress, there are more than seven lobbyists working for various parts ot the health care industry.

No hospital’s chargemaster prices are consistent with those of any other hospital, nor do they seem to be based on anything objective—like cost.

Unlike those of almost any other area we can think of, the dynamics of the medical marketplace seem to be such that the advance of technology has made medical care more expensive, not less.

“We use the CT scan because it’s a great [legal] defense. We can’t be sued for doing too much.”

And some no doubt claim they are ordering more tests to avoid being sued when it is actually an excuse for hiking profits.

Hurricane Sandy is costing $60 billion to clean up. We spend nearly that much on health care every week.

[Hospitals] have become entities akin to low-risk, must-have public utilities that nonetheless pay their operators as if they were high-risk entrepreneurs. As with the local electric company, customers must have the product and can’t go elsewhere to buy it… But unlike with the electric company, no regulator caps hospital profits.

In health care, being nonprofit produces more profit.

60% of the personal bankruptcy filings each year are related to medical bills.

25% of Americans surveyed said they or a household member have skipped a recommended medical test or treatment because of the cost.

Pharmaceutical and medical-device companies routinely insert clauses in their sales contracts prohibiting hospitals from sharing information about what they pay and the discounts they receive.

Patients don’t typically know that they are in a negotiation when they enter the hospital, nor do hospitals let them know that.

The dose of Rituxan cost as little as $300 to make, test, package, and ship, whereupon the hospital sold it for $13,702.

Give a doctor the choice between a $5 silk stitch and a $400 staple to close up an incision, and he’ll choose the $5 stitch, right? Maybe… Traditionally, knowing the costs hasn’t been part of many doctors’ medical consciousness.

People, especially relatively wealthy people, always think they have good insurance until they see they don’t.

Of New York City’s 18 largest private employers, eight are hospitals and four are banks.

More than $280 billion will be spent this year on prescription drugs in the U.S. If we paid what other countries did for the same products, we would save about $94 billion a year. The pharmaceutical industry’s common explanation for the price difference is that U.S. profits subsidize the research and development of trailblazing drugs that are developed in the U.S. and then marketed around the world. Apart from the question of whether a country with a health-care-spending crisis should subsidize the rest of the developed world—not to mention the question of who signed Americans up for that mission—there’s the fact that the companies’ math doesn’t add up.

As a perpetual gift to the pharmaceutical companies… Congress has continually prohibited the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services from negotiating prices with drugmakers.

Where Medicare has been allowed to conduct a competitive-bidding pilot program, it has produced savings of 40%.

In 1965, the House Ways and Means Committee predicted that the program would cost $12 billion in 1990. Its actual cost by then was $110 billion. It is likely to be nearly $600 billion this year.

One of the benefits attending physicans get from many hospitals is the opportunity to cruise the halls and go into a Medicare patient’s room and rack up a few dollars. In some places, it’s a Monday morning tradition. You go see the people who came in over the weekend.

The best way to both lower the deficit and help save money for patients would be to bring near seniors into the Medicare system before they reach 65… if that logic applies to 64-year-olds, then it would seem to apply even more readily to healthier 40-year-olds or 18-year-olds. This is the single-payer approach favored by liberals and used by most developed countries.

Unless you are protected by Medicare, the health care market is not a market at all. It’s a crapshoot. People fare differently according to circumstances they can neither control nor predict.

This is not about interfering in a free market. It’s about facing the reality that our largest consumer product by far—one-fifth of our economy—does not operate in a free market.

Trial lawyers who make their bread and butter from civil suits have been the Democrat’s biggest financial backer for decades. Republicans are right when they argue that tort reform is overdue.

There is little in Obamacare that addresses the core issue or jeopardizes the paydays of those thriving in a market that doesn’t work. In fact, by bringing so many new customers into that market by mandating that they get health insurance and then providing taxpayer support to pay their insurance premiums, Obamacare enriches them. That, of course, is why the bill was able to get through Congress.

Obamacare does some good work around the edges… But none of it is a path to bending the health care cost curve.

Put simply, with Obamacare we’ve changed the rules related to who pays for what, but we haven’t done much to change the prices we pay.

We’ve allowed the lobbyists and allies to divert us from the obvious and only issue: “All the prices are too damn high.”

I don’t agree with Brill’s politics nor with all his recommendations. If given a clean sheet of paper, I don’t think I would come up with single-payer (“Medicare for everyone”) as my recommendation. But we don’t have a clean sheet of paper. We’re locked in a system that makes some players very very wealthy, and makes many individuals poorer, sicker, or dead. We have to break the gridlock both as a matter of ethics and as a matter of national security.

For various historical reasons, the United States has converged onto a healthcare system that is uniquely bad among industrialized nations. (Please: before you start throwing “best healthcare system in the world” at me, read the article. And maybe travel a bit, too. Yes, you can get superb care in the United States. But we can’t afford to continue delivering it at these costs.)

And those of you who know my raving-libertarian streak will understand how offended I am, politically and philosophically, by anything that looks like “socialized medicine” (another epithet that has lost meaning through repetition).

Think how badly our system must be broken for someone like me to say that “Yes, single-payer wouldn’t be perfect, but it would be better than what we have now.”

Think about it.

“As with the local electric company, customers must have the product and can’t go elsewhere to buy it… ” — The problem is that this is not true. I “shop” for hospitals and only go to ones which have policies and prices I find agreeable. Short of being completely unable to speak, which is the great minority of ER visits, most consumers do have a choice. I’ve been in 15+ care wrecks (not driving), and that is only the tip of the ice berg for emergency room visits for me. The first thing the ER guys ask me is “what hospital do you want?”.

The fact that the author missed such a basic thing makes me question this rest. Was he really reporting or was he just collecting a sprinkling of supposed “Facts” which supported the viewpoint he planned to reach before he ever sat down to write the article?

The electric company is also a very poor analogy. They have a single product, and even then the issues surrounding pricing are VERY contentious (look at the frequent battles between SC and the PFC here in our state).

Yes, the prices are high. The government already handles the majority of medical payments. In what other industry would we argue that, when prices are too high, we give the dominant player 100% of the market to bring costs down?