This is going to be a more personal post than usual. Nine months ago today, my life changed. I went in for eye surgery. A lot of people ask questions, usually with positive assumptions like “So your eye is all better now?” It’s not, and I hate telling people that, so I decided to put it all here on my blog.

First off, people ask if this was elective or non-elective surgery. The answer is, “somewhere in between.” It wasn’t purely elective, like LASIK. (I did that back in 1998… you can read about that experience here.) At the same time, it wasn’t emergency surgery, like you’d have after a car accident or something.

I had a degenerative retinal condition called “macular pucker” in my left eye. That’s scar tissue that forms on the eye’s macula, located in the center of the retina. No one knows what causes it. A macular pucker can cause blurred and distorted central vision. For me, the primary symptom was that parallel lines weren’t parallel anymore. This gives you an idea of what I saw out of my left eye.

Since I like living in a Euclidean universe, this was disturbing to me. About two years ago, the Emory Eye Clinic correctly diagnosed the condition, and laid out my options. They boiled down to “live with it” or “surgery.”

I “lived with it” through 2009, but it was getting progressively worse. I found myself keeping my left eye closed a lot to avoid the distortion and confusion. I read up a lot on the condition, and talked to a couple of people who had had successful surgical correction. Finally, at my December 2009 appointment, I decided to go ahead and schedule the surgery.

First off, we had to order the equipment. It turns out that, for retinal surgery, you have to perform what’s call a “vitrectomy” — in layman’s language, you suck all the goop out of your eyeball and replace it with artificial goop. (In between, they’re removing the scar tissue at the back of your eyeball. I try not to think about this step, but I assume it involves very small tweezers.) Recovery involves partially filling the eye with the artificial goop, then filling the rest with a pressurized air bubble. It’s important to keep this air bubble against the back of the eye, so you have to recover face down.

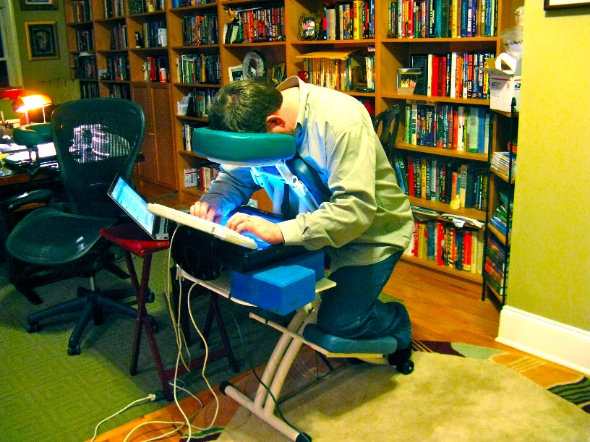

I was lucky, and only had to be face down for a few days after surgery; some people have to do it for two weeks! My surgery took place six weeks before Apple launched their iPad; if anyone is scheduling similar surgery today, I hope to heck they buy one to use during recovery. I lashed up a laptop and an external VGA monitor, but it wasn’t pretty.

So you have to rent The Chair, and The Face Cushion, and other assorted implements of discomfort. It turns out there’s a whole ecosystem dedicated to renting equipment vitrectomy patients. Somewhat depressingly, all the patient models on their websites look a lot older than me.

So we rented the chair and a few other bits, and went in for the surgery on February 23, 2010. Emory was as competent and reassuring as ever; my consciousness went to wander wherever it wanted to for a while, and I woke up in the post-op room with an enormous bandage taped to my left eye.

I don’t remember much about the next couple of days… I was on enough drugs to just drift in and out of consciousness. Post-op visit the day after surgery, and they removed the bandage. Apparently, according to my much-suffering wife, the eye looked like hamburger… which is normal. There was some blood swirling around behind my lens, which apparently wasn’t quite normal, but everyone was calm and said it would clear up on its own. (Cue the theme music from Jaws…) But now we started a complex and ever-changing series of eyedrops that continues to this day. At one point, I was on seven different kinds of eyedrops, all on different schedules (this one, every three hours; this one, twice a day; this one, one drop every other day… yikes). Some of them feel like dripping battery acid into your eye. Ouch.

By Saturday (four days after the surgery, the air bubble had been mostly absorbed, and the eye was filling back up with natural goop (okay, okay, “vitreous jelly”). But there were problems. The migraines had started. I was so nauseous that I couldn’t keep food down. (During this whole odyssey, I wound up losing 26 pounds.) Sitting very still helped, but I had to go to Emory almost every day for checkups… asking your wife to pull over now so you can throw up on the side of Briarcliff isn’t fun. And the pain was getting worse. A lot worse. By a week after surgery, I was in the emergency room, begging for an IV of morphine. Morphine plus phenergan (anti-nausea drug) plus some vitamins and a couple of bags of saline to fight dehydration. We wound up doing that more than once.

Nine months later, it’s thankfully hard to remember the pain clearly. But from notes I dictated at the time, it was “as if my eyeball had been replaced with a glowing coal from the barbecue grill.” That was continuous, 24/7. Now, I’ve had migraines since I was seven years old, and I’ve amazed doctors before with my high pain tolerance. This was a different world. I wound up with a combination of serious oral painkillers and the occasional morphine shot to get through.

In parallel with all this, I became exceptionally light-sensitive. Cissa had to go buy light-blocking plastic curtains designed for photographic darkrooms. The bedroom was lit only by the red glow from my LED alarm clock. (I actually have two alarm clocks. One has blue fluorescent numbers. Had to unplug that one; too painful. Seriously.)

A week after surgery, I started taking additional drugs (oral plus more eyedrops for high intraocular pressure; more on that below.) The pain got worse. I stopped sleeping. By two weeks after surgery, I was desperate for some sort of relief… so, wearing a pirate’s eyepatch plus a towel over my head, Cissa drove me to an acupuncturist. That didn’t do any good at all, and we were leaving there for yet another visit to the ER to get a shot of morphine. We were able to get my eye surgeon on the phone, and he asked us to come into the clinic instead.

This was the first time we’d seen the surgeon since the pain started getting so bad… he was on vacation. I don’t begrudge anyone their vacation time, but I wish I’d known that he was going to disappear the week after my surgery. Previous visits to the clinic had been handled by retinal fellows or interns. (One of whom gave me particularly unhelpful prescription for oral meds when one of my complaints was nausea so bad that I couldn’t keep anything down. So I dutifully took my pills and threw them up again. Sigh. I should have thrown a red flag at that point. Hindsight…)

So the surgeon took a look at me and measured my intraocular pressure. This is just like checking the pressure of your tires, except that the pressure gauge is a tonometer, a glowing blue cylinder that they press against your cornea. (Pro tip: opthamologists will claim that this cylinder merely gets “very close” to the surface of your eye. They’re lying; it touches.) “Normal” pressure is 15.5 mmHg. Anything over 21 mmHg is glaucoma. Anything over 30 is a real problem.

My pressure was over 50.

No wonder my eyeball felt like it was about to explode! It turns out that my eye’s natural drainage system had gotten blocked by stray blood from the surgery, so the pressure just kept building and building. That caused direct pain, as well as the nausea and other symptoms (which is why glaucoma patients can smoke pot in California).

There was no way to physically clear out the drain other than surgery, but we could at least let some air out of the overinflated tire. My surgeon called in another retinal fellow (it’s 10:00 at night by this point) and proceeded to stick a hypodermic needle in my eye to draw off some excess fluid. This sounds incredibly painful. It was. And, being awake the whole time, I got to see it (unlike the original surgery) while concentrating on remaining very very still. I don’t recommend it. It’s an indication of how much I was hurting that — when the doctors were dithering over whether to intervene or practice “watchful waiting” — I was begging them to stick the needle in my eye. Begging.

This was the turning point. But I wasn’t out of the woods. My intraocular pressure plunged from 50 to 3, so they took me off most of the pressure-reducing eyedrops, but I needed to come back every day for the tonometer tests. We wound up visiting the Emory Eye Clinic 27 times in the month of March, which they claimed was an all-time record. Slowly, my eye pressure rose back into the teens, where they were able to stabilize it by going back on some of the eyedrops. I was taking six Percocets and three Oxycontins a day. I don’t remember much. I know that I wasn’t eating; I was basically living on Gatorade. Great weight loss program, if you can survive it.

Keep in mind that this whole process was supposed to take two weeks; I had cleared my calendar, and was confident I’d be back at work by March 8th. Obviously, that didn’t happen.

A month after the surgery, there was an important meeting at the office that I felt I really needed to attend. I dressed up in my piratical best (although I reluctantly left the parrot at home) and Cissa dropped me off in front of the Tech Tower. I participated quietly in a 45-minute meeting. As soon as I got home, I slept for four hours. No energy reserves at all.

I didn’t get back to a full day in the office until April 1, nearly six weeks after surgery. And, for most of that time, I was in a very dark room, unable to read or to use a computer. Luckily, I have a superb senior staff who kept everything running smoothly. And after logging back into 4000 unread emails, I just archived everything and assumed that anything really important would show up again.

By mid-April, I was off all the narcotics and half the eyedrops. My vision seemed to have stabilized… but was lousy. Worse than it was before the surgery. Emory Eye Clinic conducted a bunch of tests, and came to a depressing conclusion: The extended period of high intraocular pressure had damaged my optic nerve. So, even though the retinal repair was successful, the shiny-new retina wasn’t connected to the brain very effectively. My peripheral vision on the left side was shot, the lower half of my field of view was shot, and the rest was pretty blurry.

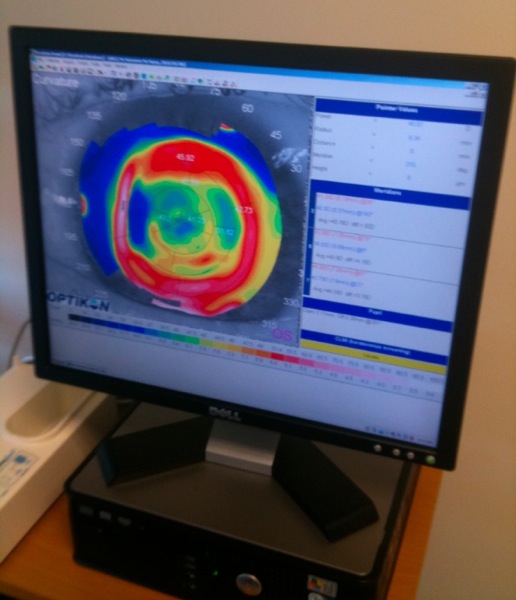

That’s at the back of the eyeball; the front wasn’t much better. See this screenshot?

That’s a topographical map of my left cornea. It’s supposed to be a nice smooth spherical surface. Mine looks like craters of the moon. Best guess is that my ancient LASIK procedure had weakened the cornea enough that, when my intraocular pressure whipsawed up to 50 and down to 3, the corneal surface got distorted and didn’t entirely recover.

We pursued a bunch of things over the next few months, including new glasses and even contact lenses. And a dizzying array of eyedrops. Nothing worked. In order to get a completely independent opinion, I even visited an opthamologist in Brazil while we were in the country for a family wedding.

Sadly, he agreed with the Emory docs: Permanent damage to the optic nerve. My only real hope is for stem cell therapy to mature rapidly enough that I can take advantage of it. Given the political situation in the USA, that probably means a trip to France or Germany. Optimistically, five years; realistically, 10 to 15. Fingers crossed.

Added bonus attraction: One of the known side effects of a vitrectomy is accelerated likelihood of cataracts. That’s happened to me pretty quickly, so sometime in the next year or so, I’ll have to have the cataract removed from my left eye. That’s much more routine than retinal surgery… but one of the side effects of cataract surgery is increased intraocular pressure! So my cataract surgery may have to be combined with glaucoma surgery to provide a pressure vent; we don’t ever want my pressure spiking again, since it’s already done so much damage to the optic nerve. That means a much more complicated surgical procedure and recovery period. I can hardly wait.

In the meantime, I can’t see very well. The best analogy I can give is:

Imagine smearing a thick coating of Vaseline all across your eyeglass lens. That’s what the world looks like to me when I close my right eye… with or without glasses/contacts. Removing the cataract will help a little, but not to the point where I can read comfortably with my left eye (I keep it closed a lot), or even enjoy the next Avatar movie in 3D. But it will keep me using that eye, rather than just mentally “turning it off”… I want to keep it as functional as possible while waiting for stem cell treatment.

It turns out the human brain is smart enough to adapt to almost anything, so I’m pretty much completely functional. The times I really notice it is when riding my bike (cars come up on the left, where I have no peripheral vision) or when reaching for a nearby object (no depth perception means I knock over a lot of water glasses and salt shakers). Mostly, I’m managing fine, and there are millions of people on Earth with much worse vision problems. I can’t complain.

But if I could go back to February and convince myself to live with wavy parallel lines… I would.

I totally identify with your experience Steven, but thankful haven’t had the pain or drama you’ve experienced! One trick that I learned after doing the pirate thing (it just couldn’t be accessorized which killed me) for a year and winking at everyone all the time as I closed one eye so I could manage to walk – simply cut a piece of clear contact paper and place it over the lenses of your glasses. It isn’t really clear – sort of frosted – and it works wonderful!! It is just enough to trick your brain. Of course people are constantly telling you that your glasses are smudged, but that is so much easier to manage than an uncomfortable eye patch and it does the trick!

Stephen,

I am so sorry to hear you had to go through all that. That is a brutal tale to read. I am glad you are feeling better – although not fully recovered. I thought my 30 month fight to recover from a degeneraative disk problem and back injury was a brave fight. But alas – not even in your league. You are one tough cooky my friend.

God bless.

Keith