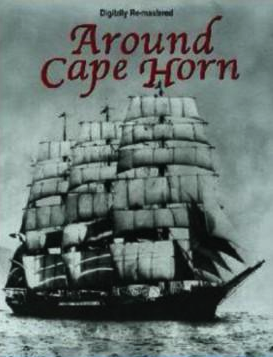

Over the Christmas break, I found myself watching this video: “Around Cape Horn.” As a young man, Irving Johnson sailed aboard the barque “Peking” in 1929, as the sun set on the day of commercial sail. And he carried a movie camera.

There’s amazing footage of storms off Cape Horn, as well as less stressful footage of daily life on board one of the last commercial sailing ships: no engines, no electricity, no hydraulics, no GPS, no radio (except, probably, a short range Morse-code rig). Oil lamps and a hand-cranked foghorn. Over an acre of sails were controlled by a crew of dozens of young men swarming up and down her four masts, up to 170 feet above the sea. Four hours on, four hours off, for a hundred days. Lousy food and worse sanitation.

All this within living memory. Of course, my first reaction was admiration for the strength and endurance of the crew. But then I began to think about all the skills required by the underlying technology base that permitted three dozen men to transport three tons of cargo around the world using wind, muscle power, and ingenuity. How almost every item and every task on board would have been instantly familiar to Lord Nelson after Trafalgar in 1805.

And about how all of those skills have been lost within one human lifetime.

I’m exaggerating. I suppose the skills aren’t really “lost.” There are plenty of books, and journals, and even courses on the Age of Sail. But these are intellectual curiosities. We no longer have an industrial base whereby thousands of sailors, and tens of thousands of at-shore workers, rely on commercial sailing ships. So, of course, as far as the job market is concerned, the skills have been lost.

It’s true in every field. No one other than historical re-enactors knows how to make a buggy whip. Or a suit of armor. Or a flint knife. Heck, just ask any office worker of a certain age for a sheet of carbon paper! (My mom typed the board minutes of the Trust Company of Georgia, now SunTrust, every month. Twelve copies, eleven sheets of carbon paper. As you can imagine, she learned to type very accurately without touching the backspace key!)

Those aren’t commercially-useful skills anymore. So we don’t learn them, and we don’t teach them.

What do we teach? Look at the last resume that crossed your desk. It probably has a line saying something like “Proficient in Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint.” You can get a degree from Harvard with your sole “quantitative reasoning” class being “Practical Math,” which appears to be a review of basic arithmetic plus tips for using Microsoft Excel.

Does anyone really believe that Microsoft Excel will be a core skill set in forty years? Twenty years? It’d be like telling the first mate on a modern merchant marine ship that you know how to repair a canvas sail by hand.

But, like sailing a barque around Cape Horn by hand, what have we lost? I used to know how to do basic car maintenance. Changed my own oil. Changed fan belts. Changed plugs, points, and condensers. This isn’t special; probably every American male born in the Fifties and early Sixties learned the same. Now, I open the hood of a modern automobile and am baffled by the complexity. So I take it to the dealer, who has $15,000 worth of computer equipment to diagnose its ills. We’re probably not far from the day when, like your iPhone, your car requires special tools just to open the hood.

I’m pretty much the opposite of a Luddite. I think that, in general, new technology makes our lives better… and that when technology has unpleasant consequences (like pollution), the answer is usually more technology, not less. But watching this video, my mind filled in a Jimmy Buffett soundtrack… “Watched the men who rode you switch from sails to steam.” And I wonder if we’ve lost something worth keeping?

Awesome read, Stephen, thanks for sharing! As a kid who was born in the 60s, I totally agree. The infusion of technology under the hood of a car is what killed my dad’s automotive machine shop, which he ran for 30 years.

I volunteer restoring old airplanes, and it amazes me that some of the stuff still works and how under appreciated it is. We fly a 1918 Le Rhone Rotary Engine (of which maybe 50 still fly), and a late WW1 Rolls Royce Eagle VIII which is the only running one of its kind. Whenever I give tours I’m sure to point out “It is the last of it’s kind” and people are never really as amazed about it as I would hope.